I Built an OpenClaw Agent to Understand What Developers Are Actually Doing (Not Because I Needed One)

By Chukwuma Onyeije, MD, FACOG

Maternal-Fetal Medicine Specialist | Founder, CodeCraftMD | Atlanta Perinatal Associates

Here’s the truth about being a physician-developer: you learn by breaking things on purpose.

Earlier this week, I set up an OpenClaw agent on Cloudflare. Not because my clinical workflow desperately needed it. Not because I had some grand vision of autonomous medical AI. But because software developers are actively using agent frameworks, and I wanted to understand why before I dismissed it or—worse—adopted it blindly.

Cost? About $5/month for Cloudflare hosting plus whatever API credits I burn through with Claude.

Current use case? Tracking my blood glucose patterns for my Performance Glycemic Intelligence System (PGIS) as I train for a half marathon later this year.

Do I think I’ll use this long-term? Probably not.

Was it worth it? Absolutely.

Let me explain.

The Physician-Developer Learning Model: Try It Before You Judge It

There’s a specific kind of professional whiplash that happens when you practice medicine and write code:

Clinical medicine rewards deep expertise in established patterns. You master guidelines, refine judgment, build on decades of evidence.

Software development rewards exploratory breadth. You try new frameworks, you break them, you understand their failure modes, then you move on.

When physicians encounter new AI tools, we often do one of two things:

- Adopt them uncritically because “everyone’s using it”

- Reject them categorically because “it’s not validated”

But there’s a third path: informed experimentation.

That’s what OpenClaw was for me—a controlled experiment to understand what developers are doing with autonomous agents before it shows up in my clinical software stack wrapped in marketing promises.

What OpenClaw Actually Is (The Non-Marketing Version)

Let me strip away the hype:

OpenClaw is a self-hosted agent framework that lets you run AI assistants on infrastructure you control. It consists of:

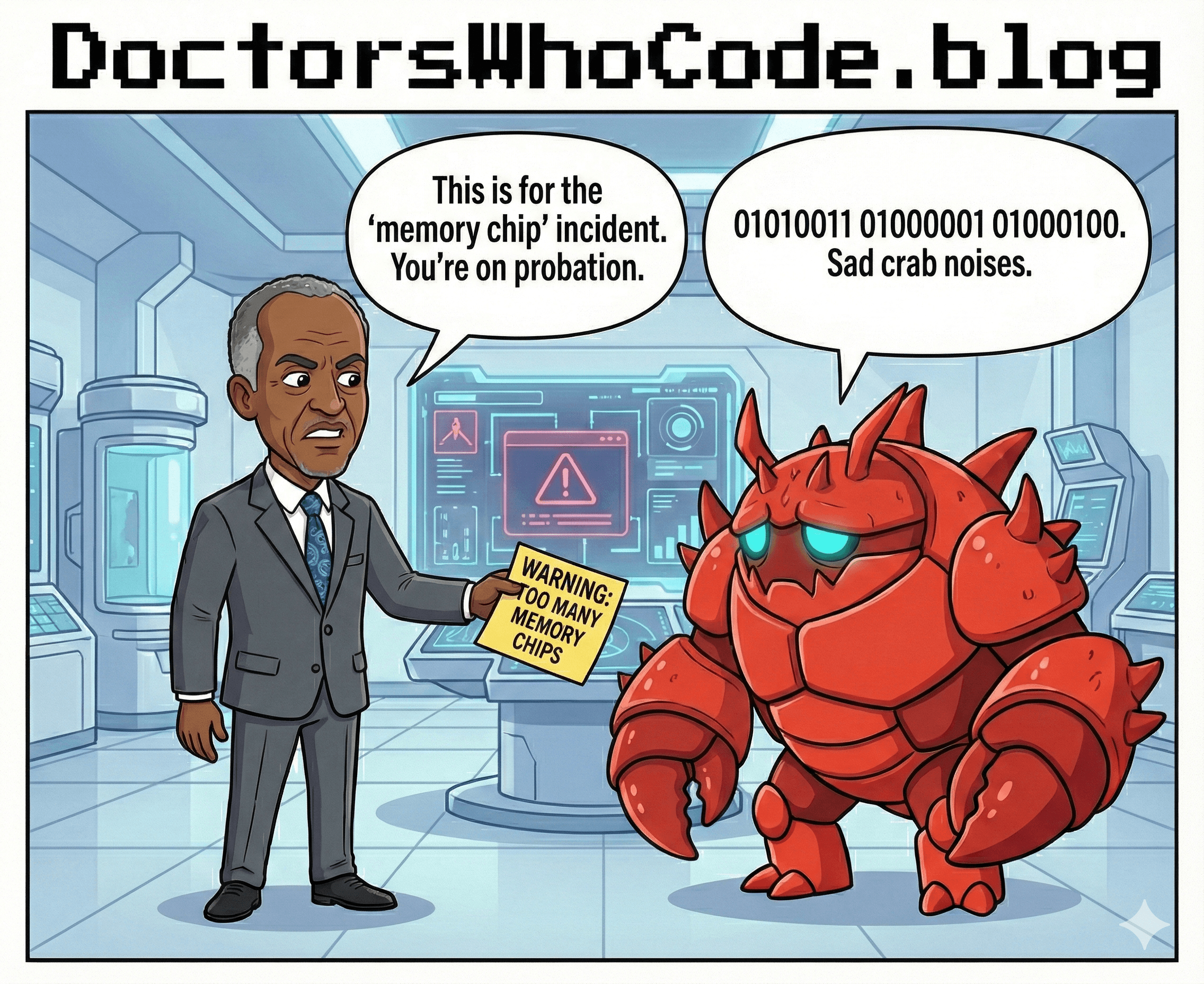

- Clawdbot: The agent runtime and orchestration layer – first iteration. Claude was NOT happy with the name

- MoltBot: The personality/behavior configuration layer – second iteration – The name was panned (universally)

- OpenClaw: The deployment pattern for self-hosting

Think of it as: “What if ChatGPT lived on your server, remembered context across sessions, and could execute tasks autonomously?”

The appeal for developers is obvious:

- No vendor lock-in

- Persistent memory

- Tool integration

- Infrastructure control

The risks are equally obvious:

- You’re responsible for security

- You manage the failure modes

- There’s no support ticket to file when it breaks

As a physician, I’m acutely aware that “autonomous” and “medical” should rarely appear in the same sentence. But as a developer, I needed to understand what “autonomous agent” actually means in practice—not in theory.

Why I Chose Cloudflare (Practical Constraints, Not Philosophy)

I didn’t run this experiment on:

- A random VPS (too much security overhead)

- My personal laptop (defeats the “always available” test)

- A closed SaaS platform (misses the point of self-hosting)

I chose Cloudflare for boring, practical reasons:

- Low friction setup (I have ~6 hours/week for side projects)

- Reasonable security defaults (I’m not a security engineer)

- Observable behavior (I can see what it’s doing)

- Low cost commitment ($5/month—easy to abandon)

- Edge-based execution (wanted to test latency claims)

This wasn’t an architectural manifesto. It was “let me spend one Saturday seeing if this works.”

It did work. Now I understand why developers are excited about it—and why I’m probably not going to use it long-term for anything serious.

What I’m Actually Using It For: My Performance Glycemic Intelligence System

Full transparency: I have Type 2 diabetes that I manage through diet, exercise, and monitoring. I’m training for a half marathon later this year, which means I’m deeply interested in how my glucose responds to:

- Different workout intensities

- Pre-run fueling strategies

- Post-run recovery windows

- Sleep quality impacts

My Performance Glycemic Intelligence System (PGIS) is essentially:

- Continuous glucose monitor data

- Training logs (distance, pace, heart rate)

- Food intake records

- Sleep tracking

- Pattern recognition to optimize performance

The OpenClaw agent helps me:

- Parse CGM exports into readable summaries

- Flag unusual glucose patterns relative to workouts

- Remind me to log meals on training days

- Track trends over weekly cycles

Is this something that requires a self-hosted autonomous agent? Absolutely not.

Could I do this with a spreadsheet, Python script, or even ChatGPT? Yes.

But that misses the point of the experiment. I wanted to understand:

- How agent memory works across sessions

- What “autonomous” actually means in practice

- Where the friction points are

- What failure modes look like

Now I know.

What I Learned (That I Couldn’t Learn by Reading Documentation)

1. “Autonomous” Is Oversold

Agents don’t actually work autonomously in any meaningful sense. They:

- Execute predefined patterns

- Wait for human approval at decision points

- Break on edge cases constantly

- Require more supervision than advertised

The marketing says “autonomous.” The reality is “batch processing with conversational UI.”

2. Memory Is Messier Than Advertised

Persistent memory sounds great until you realize:

- The agent “remembers” things you didn’t want it to

- It forgets context you assumed was retained

- Memory becomes noise over time

- You need explicit memory hygiene practices

This is exactly the kind of thing that would be dangerous in clinical contexts.

3. The Value Is in Context Switching, Not Autonomy

The actual benefit isn’t that the agent “does things for me.” It’s that when I return to my PGIS work after a week of clinical shifts, the agent can:

- Remind me where I left off

- Summarize what changed since last session

- Reduce the cognitive load of context recovery

That’s not autonomy. That’s persistent context—and it’s legitimately useful.

4. Tool Integration Is the Real Unlock

The interesting part isn’t the agent itself. It’s how easily it can:

- Read files

- Parse data

- Execute scripts

- Format outputs

This is what developers have been doing with APIs for years. The agent just adds a conversational layer on top.

The Guardrails I Used (Because I’m Still a Physician)

Even in a personal, non-clinical experiment, I built constraints:

No Patient Data, Ever

The agent has zero access to anything resembling patient information. This is a hard boundary.

Explicit Approval for Any Action

The agent cannot:

- Modify files automatically

- Send messages on my behalf

- Execute code without confirmation

Session-Limited Memory for Sensitive Data

My glucose data is personal health information. The agent can reference it within a session, but I manually clear memory between sessions.

No Clinical Decision Support

This system provides pattern recognition, not medical advice. I make all decisions about my diabetes management with my actual physician.

Will I Keep Using OpenClaw? Probably Not.

Here’s the honest assessment after two months:

What worked well:

- Easy to set up (took about 4 hours including learning curve)

- Low ongoing cost ($5/month Cloudflare + ~$10/month Claude API)

- Helped me understand agent architecture

- Useful for understanding developer enthusiasm

What didn’t work well:

- Required more maintenance than expected

- Memory management became tedious

- Overkill for my actual use case

- Better solutions exist for PGIS specifically

Will I keep it running?

Probably not past this training cycle. Once I understand the pattern, I usually move to the next experiment.

That’s the point of being a physician-developer who learns by doing—you don’t need to adopt every tool permanently. You need to understand it well enough to evaluate it critically.

What’s Next: The Pattern Continues

This is part of a larger pattern in my learning process:

- Built CodeCraftMD to understand medical billing automation

- Created PreEclampsiaWatch to understand real-time risk monitoring

- Deployed OpenClaw to understand autonomous agents

- Next up: Probably whatever framework developers move to next

I don’t expect to use all of these long-term. But I need to understand them before they show up in:

- EMR vendor pitches (“We’re adding AI agents!”)

- Hospital IT rollouts (“This will improve efficiency!”)

- Clinical decision support tools (“FDA-cleared autonomous monitoring!”)

When a vendor tells me their product uses “autonomous agents,” I now know:

- What that actually means

- What the failure modes are

- What questions to ask

- What guardrails should exist

That knowledge cost me $5/month and a few Saturdays. Worth it.

Why This Matters for Other Physician-Developers

If you’re a physician who codes, you already understand this: the best way to evaluate technology is to build it yourself.

Not because you’ll use your version in production. But because:

- You learn the constraints (what’s actually hard vs. what’s marketing)

- You understand failure modes (before they affect patients)

- You ask better questions (when vendors pitch you AI tools)

- You maintain technical literacy (in a field that moves fast)

OpenClaw won’t be my last experiment. It probably won’t even be the most useful one.

But it taught me what I needed to know: what autonomous agents actually do, where they break, and why developers are excited about them.

Now when someone pitches me “AI agent-powered clinical workflow,” I won’t be impressed by the buzzwords. I’ll ask about their guardrails, their memory architecture, and their failure recovery.

Because I’ve already broken those things myself.

The Experiment Continues

My OpenClaw agent is currently tracking my glucose patterns as I build toward my half marathon goal. It’s doing fine. A Python script would do just as well.

But the experiment wasn’t about finding the perfect tool.

It was about understanding what happens when physicians stop being passive consumers of AI tools and start being active evaluators of AI architecture.

Next experiment? Probably whatever framework developers move to after agents. Maybe local LLMs. Maybe multimodal reasoning systems. Maybe something that doesn’t exist yet.

The cost will be low. The time investment will be bounded. The learning will be priceless.

Because in medicine, the worst thing you can be is technically illiterate in a field that’s technically evolving.

I’d rather break things intentionally in my home lab than watch them break unexpectedly in my clinical practice.

Closing Thought: Learn by Building, Evaluate by Breaking

You don’t need to run your own OpenClaw agent.

But if you’re a physician who codes, you should probably run something that helps you understand what developers are building—before it shows up in your EMR with a support contract.

My PGIS experiment will probably end when my half marathon training does.

But the pattern will continue: try it, break it, understand it, evaluate it, move on.

That’s how physician-developers stay ahead of the curve instead of getting run over by it.

Current Status:

- OpenClaw agent: ✅ Running (for now)

- PGIS tracking: ✅ Active

- Half marathon training: 🏃♂️ Thanksgiving 2026

- Next experiment: 🤔 TBD

Want to compare notes on physician-developer learning experiments? Have you tried building something just to understand it? Let me know what you’re testing.

About the Author

Chukwuma Onyeije, MD, FACOG, is a board-certified Maternal-Fetal Medicine specialist and Medical Director at Atlanta Perinatal Associates. He founded CodeCraftMD, an AI-powered medical billing and documentation platform, and writes about physician-built healthcare technology at lightslategray-turtle-256743.hostingersite.com. He learns by building, evaluates by breaking, and trains for half marathons while managing Type 2 diabetes through his Performance Glycemic Intelligence System.

Currently running OpenClaw for PGIS tracking. Ask me again in 3 months if I’m still using it.

Tags: #PhysicianDeveloper #OpenClaw #LearningByDoing #PGIS #Type2Diabetes #HalfMarathonTraining #AIAgents #DoctorsWhoCode #ClinicalInformatics #HealthTech